I slumped in an unpadded pew, half-listening to the morning Bible study. I wasn’t particularly interested in what the Bible teacher in this small Christian high school had to say. But, when the teacher commented that the Gospels always reported word-for-word what Jesus said, I perked up and lifted my hand. This statement brought up a question that had perplexed me for a while.

“But, sometimes,” I mused, “the words of Jesus in one Gospel don’t match the words of the same story in the other Gospels—-not exactly, anyway. So, how can you say that the Gospel-writers always wrote what Jesus said word-for-word?”

The teacher stared at me, stone-silent.

I thought maybe he hadn’t understood my question; so, I pointed out an example that I’d noticed—-the healing of a “man sick of the palsy” in Simon Peter’s house, if I recall correctly (Matthew 9:4-6; Mark 2:8-11; Luke 5:22-24, King James Version).

Still silence.

Finally, the flustered teacher reprimanded me for thinking too much about the Bible. (In retrospect, this statement was more than a little ironic: A Bible teacher in a Bible class at a Bible Baptist school accused me of thinking too much about the Bible!) What I was doing, he claimed, was similar to what happened in the Garden of Eden, when the serpent asked Eve if God had actually commanded them not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge.

I didn’t quite catch the connection between my question and the Tree of Knowledge—but I never listened to what that teacher said about the Bible again. I knew that something was wrong with what he was telling me. Still, it took me several years to figure out the truth about this dilemma—a truth which, just as I suspected, had everything to do with the teacher’s faulty assumptions about the Bible and nothing to do with Eve or the serpent.

Here’s what my Bible teacher assumed: If the Bible is divinely inspired, the Bible must always state the truth word-for-word, with no variations. To question this understanding of the Bible was, from this teacher’s perspective, to doubt the divine inspiration of Scripture.

::”WE HAVE ONLY ERROR-RIDDEN COPIES”::

Oddly enough, when it comes to differences between biblical manuscripts Dr. Bart Ehrman, James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, seems to follow a similar line of reasoning in his book Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why–but with opposite results. Ehrman, unlike my high school teacher, is fully aware of differences not only between different accounts of the same events but also between the thousands of New Testament manuscripts. Because these variations between biblical manuscripts do undeniably exist, the New Testament cannot be—in Ehrman’s estimation—divinely inspired. And this is where he expects from Scripture the same as what my teacher expected but with opposite results.

How does it help us to say that the Bible is the inerrant word of God if in fact we don’t have the words that God inerrantly inspired, but only the words copied by the scribes—sometimes correctly but sometimes (many times!) incorrectly?

Ehrman is correct that the original New Testament writings (the “autographs”) disintegrated into dust long ago (though they did last at least until the early third century—but that’s a subject for another blog post). He’s also correct that the copies of the New Testament documents differ from one another in thousands of instances. Where Ehrman errs is in his assumption that these manuscript differences somehow demonstrate that the New Testament does not represent God’s inspired truth. The problem with this line of reasoning is that the inspired truth of Scripture does not depend on word-for-word agreement between every biblical manuscript or between every parallel account of the same event.

In the first place, the notion of word-for-word agreement is a relatively recent historical development. In times of antiquity it was not the practice to give a verbatim repetition every time something was written out. To be sure, I don’t believe that one passage of Scripture ever directly contradicts other passages. Yet, when someone asks, “Does everything in Scripture and in the biblical manuscripts agree word-for-word?” that person is asking the wrong question. The answer to that question will always be a resounding “no.”

Instead, the question should be, “Though they may have been imperfectly copied at times and though different writers may have described the same events in different ways, do the biblical texts that are available to us provide a sufficient testimony for us to understand and reconstruct the intent of the original inspired words?” In other words, are the available copies of the New Testament manuscripts sufficiently well-preserved for us to grasp the truth that was conveyed in the first century? I believe the answer to this question is “yes.”

The ancient manuscripts were not copied perfectly. Yet they were copied with enough accuracy for us to comprehend what the original authors intended. But, if Bart Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus had been the only book I read on this subject, I might have reached a radically different conclusion.

To the casual reader, Misquoting Jesus could imply that the early copyists of the New Testament were careless. What’s more, these scribes were prone to making purposeful changes in the text for purely theological reasons. After considering Ehrman’s oft-repeated reminder that “there are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament,” I would probably be left with the assumption that the texts of the New Testament aren’t all that reliable after all.

So which is it?

Have centuries of careless copying tainted the texts beyond recovery? Or are the New Testament documents sufficiently reliable for us to discover the truths that the original authors intended? Before answering these questions, it’s necessary for us to gain a foundational understanding of how these texts were preserved in the first place. So, how were these documents kept and copied among the earliest Christians?

::FOLLOWING JESUS IN THE CHURCH’S FIRST CENTURIES::

Suppose that you are a follower of Jesus Christ at some point in the church’s first three centuries. You have chosen to entrust your life to this deity who—according to the recollections of supposed eyewitnesses—died on a cross and rose from the dead. Through baptism, you have publicly committed yourself to imitate Jesus’ life. Now, you earnestly desire to be more like Jesus.

But how?

Without easy access to writings about Jesus, how can you learn what it means to follow Jesus?

There are no Christian bookstores in the local marketplace. And, even if you could purchase a scroll that contained some of Jesus’ teachings, you probably wouldn’t be able to read it. Between 85% and 90% of people in the Roman Empire seem to have been illiterate.

How, then, can you learn more about Jesus? Besides imitating the lives of other believers, you would have learned about Jesus from written documents. But how, as an illiterate person, would you have heard these writings?

::THE FIRST CHURCH LIBRARIES::

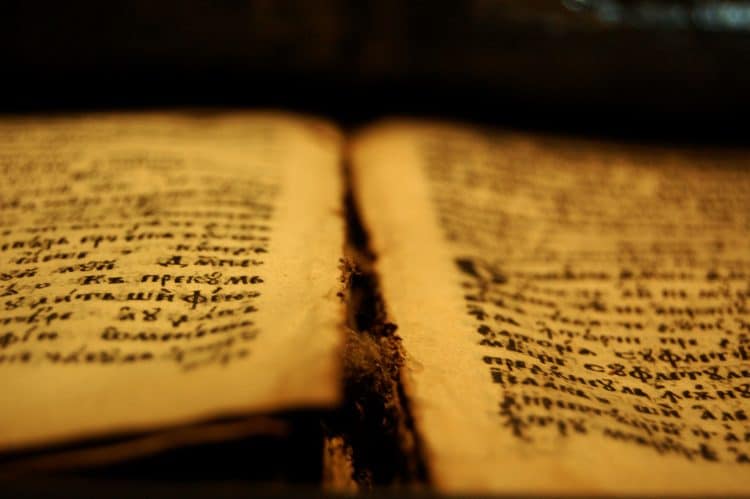

It’s important to recognize that the writings of the prophets and the apostles were so important to early Christians that they maintained libraries long before they maintained buildings. During the first century A.D., the Jewish Scriptures as well as the writings of the apostles circulated as scrolls—as strips of parchment or papyrus, rolled around a stick.

In the late first century A.D., Christians still preserved their writings in book-chests, but these writings began to take a new form: Stacks of papyri were folded and bound to form a “codex,” the ancestor of the modern book. Codices—that’s the plural form of codex—were cheaper and more portable than scrolls. Partly because churches owned no buildings and sometimes needed to move their meeting-places, the codex became a popular choice for copying the earliest Christian writings.

Thirteen letters from Paul would likely have been among the oldest codices in your cabinet, then the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and then perhaps a letter from the apostle Peter and at least one letter from John (not to mention the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament). When your congregation gathered each week, one of the literate believers would have read passages from the Jewish Scriptures—primarily from the prophets, since Christians believed these writings pointed most clearly to Jesus—and from the writings that were connected to the apostles.

But where would the writings in your church’s book-chest have come from? Most likely, none of these codices would have come directly from Paul or Matthew, Peter or John! Your church’s codices would have been copies, and these copies would have been passed to your congregation from copyists or scribes.

The first Christian copyists were simply Christians who were capable of writing. Some of them may have copied scrolls in the Jewish synagogues before they became believers; others may have reproduced Roman legal documents. At some point—probably in the second century—churches in major cities established official groups of copyists to duplicate the Christian Scriptures. And, so, the accuracy of the New Testament documents depended on hundreds of anonymous copyists—men and women whose names you will probably never know. These individuals were committed to the transmission of the New Testament because they were dedicated to the gospel message and the Great Commission. Their work continues in the efforts of translators and missionaries today, seeking to copy and proclaim the word of God for his glory so that countless more would hear (and read) about salvation in Christ alone.

For references and to learn more on the transmission of the New Testament text, order my book Misquoting Truth.

For a helpful look at Ehrman’s claims about the New Testament in popular media, click here.