In his article “For Whom Were the Gospels Written?,” Richard Bauckham points out that

a small minority group experiencing alienation and opposition in its immediate social context could compensate for its precarious minority position locally by a sense of solidarity with fellow believers elsewhere and a sense of being part of a worldwide movement destined to become the worldwide kingdom of God.

In other words, the fact that Christians in the first, second, and third centuries were marginalized and socially ostracized contributed to a pattern of cultivating communications and connections with Christians in other places. The degree to which Christians were socially ostracized has been helpfully described in books such as Larry Hurtado’s Why Did Anyone Become a Christian in the First Three Centuries? and Destroyer of the gods as well as Alan Kreider’s The Patient Ferment of the Early Church and Christianity at the Crossroads by Michael Kruger.

What I find fascinating when I consider this from the perspective of God’s providence in history is the degree to which—if Bauckham is indeed correct, and I believe that he is—persecution was thus a catalyst for orthodoxy, catholicity, and canon. Here’s what I mean: If Christians in one location never conscientiously cultivated connections with Christians in other places, their beliefs and their Bibles would have been more likely to have diverged from one another. But that’s not at all what happened in the early centuries of Christian faith. The social isolation of Christians that prevented connections within their immediate contexts produced a need for Christians in each context to connect Christians in other contexts. These connections helped Christians to become intimately aware of the books that other believers used, as well as the beliefs and practices of these other believers. More importantly, these connections kept Christians in the first and early second centuries linked to eyewitnesses who had seen and heard the words of Jesus firsthand. In the words of Bauckham, “there was so much traveling and interconnection between the Christian communities of the early decades that the Gospel traditions known to the teachers in one church would surely be widely shared.”

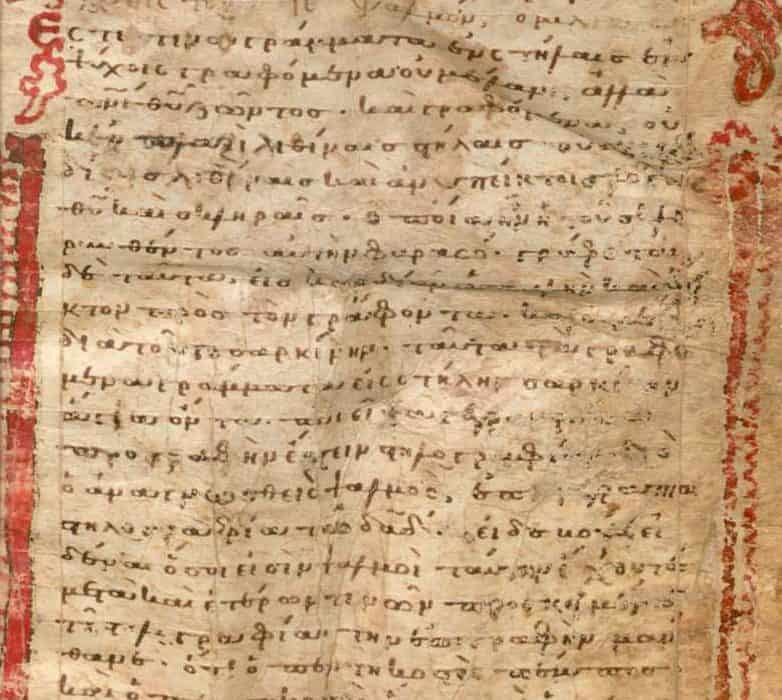

All of this contributed to a certain catholicity in the church, in the proper sense of the word “catholic”—a term that derives from a Greek phrase that means “according to the whole.” Christians were “catholic” in the sense that Christians in different places held the same beliefs and generally revered the same texts. And thus, before the end of the second century, a creed that would develop into the Apostles’ Creed and a consensus regarding the core texts of the New Testament had already emerged. By the mid-third century, Origen of Alexandria listed in one of his homilies on Joshua the precise same books that you find in your New Testament today as the authoritative canon of Christian writings. God in his providence worked through persecution to conform the church’s books and the church’s beliefs to his divine design.