The thinking of a Christian and a non-Christian diverges at the most basic level. The believer in Jesus Christ sees all of reality from the cognitive perspective of an individual who lives with “the mind of Christ” and whose life is shaped by the Word of God (1 Corinthians 2:16). This does not cause Christians to become more intelligent, more rational, or more perceptive than non-Christians. A commitment to Jesus Christ does, however, cause every fact in the universe to be seen in a different way, as a reality that exists in, for, and through Christ (Colossians 1:15-20). There is thus a fundamental epistemic distinction between the Christian and the non-Christian. In the words of Reformed theologian Cornelius Van Til, “The natural man has epistemologically nothing in common with the Christian.”

But what does this mean for meaningful engagement between Christians and non-Christians, particularly when it comes to ultimate issues such as the truth of Christianity? And what—if any—truths about God can an unbeliever know through nature or natural reason? Most importantly for those of us who live to fulfill the Great Commission—if there is a fundamental epistemic distinction between the thinking of a Christian and a non-Christian—on what basis can a Christian discuss the truth of Jesus with someone who rejects Jesus as he is described in Scripture?

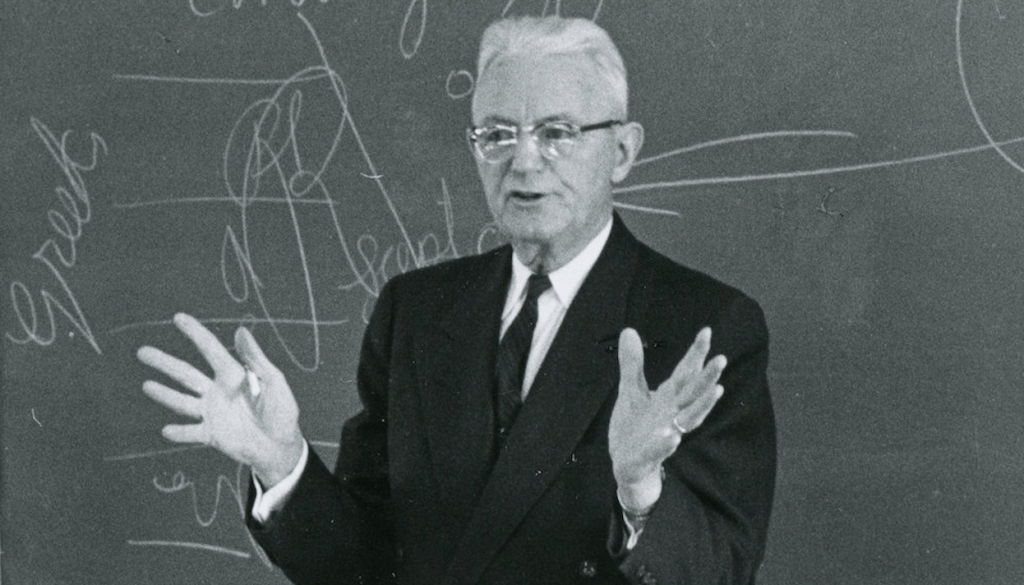

Cornelius Van Til and the Impossible Possibility of Common Ground

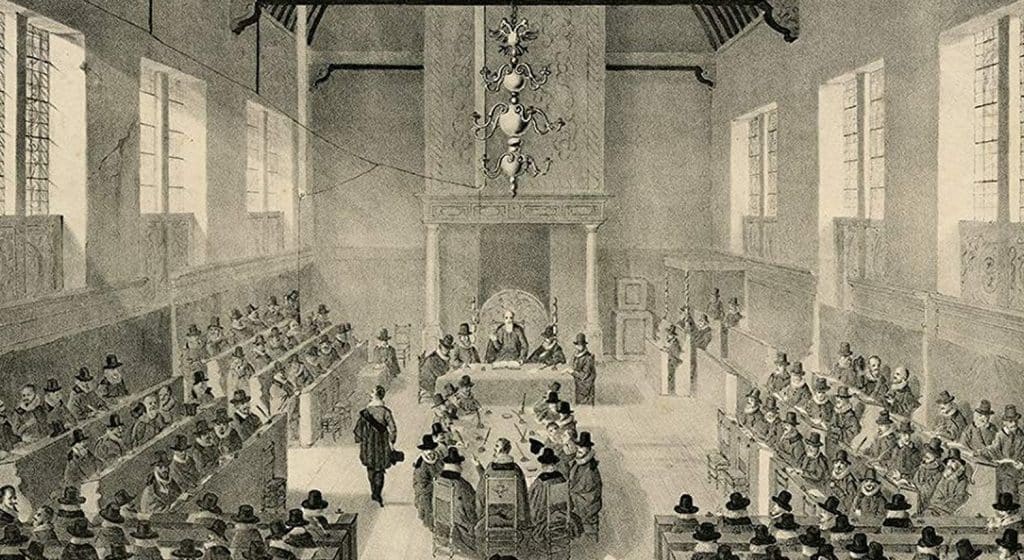

One possible response to this perennial question was articulated in 1619 at the Synod of Dordt. Here’s how the delegates at Dordt summarized their understanding of Scripture on this issue:

There is, to be sure, a certain light of nature remaining in man after the fall, by virtue of which he retains some notions about God, natural things, and the difference between what is moral and immoral, and demonstrates a certain eagerness for virtue and for good outward behavior. But this light of nature is far from enabling man to come to a saving knowledge of God and conversion to him—so far, in fact, that man does not use it rightly even in matters of nature and society.

Canons of Dordt

Sometimes, it seems as if Reformed theologian Cornelius Van Til rejected this biblical and historical understanding of “common notions.” “Christians and non-Christians,” Van Til contended in The Protestant Doctrine of Scripture, “begin their reasoning from ‘opposing first principles.’ This precludes all intelligible contact between Christians and non-Christians.” Earlier in The Protestant Doctrine of Scripture, Van Til claimed that it is impossible for anyone who embraces Reformed theology to find “common ground” with a non-Christian.

In response to such claims, a wide range of theologians have concluded that Van Til rejected the possibility of intellectual commonality between Christians and non-Christians. According to Alister McGrath, “Van Til … declares that the possibility of a dialogue with those outside the Christian faith is excluded. There is no common ground” on which the minds of Christians and non-Christians can meet (Intellectuals Don’t Need God—and Other Modern Myths).

Given Van Til’s own claims about the possibility of common ground between believers and non-believers, McGrath’s interpretation is understandable. Here, as in many other instances, Van Til’s account of his own thinking is scattered, unclear, and frequently overstated. Nevertheless, even as I disagree with many of Van Til’s assumptions and recognize his failure to communicate his ideas with clarity, I am convinced that Van Til’s system is internally coherent and that it explicitly allows for meaningful dialogue with those outside Christian faith. Whether or not this system meshes with Scripture and with other sources of truth is another issue—but Van Til’s own thinking does constitute a coherent system, unclearly articulated as it is.

In his apologetic method, Cornelius Van Til was in some sense simultaneously identifying with and distancing himself from certain aspects of the thinking of both B.B. Warfield and Abraham Kuyper. To understand Van Til on this point, it is essential first to consider the relationship of Van Til’s views to the perspectives of Warfield and Kuyper.

Van Til and the Apologetics of B.B. Warfield

Cornelius Van Til’s presentation of Warfield was incomplete at best, gratuitously inaccurate at worst. “Warfield,” claimed Van Til, “wanted to operate in neutral territory with the non-believer.” According to Van Til’s recounting of Warfield’s method, Warfield thought Christians and non-Christians share a common rational understanding that enables them to reason their way to theism from a neutral starting point. In Van Til’s view, the venerable principal of Princeton saw the process of apologetics as something like the construction of a building from concrete blocks. In this approach, which Van Til dubbed “block house” apologetics, a believer first demonstrates the existence of God on the basis of a neutral foundation and then builds a case for the rest of Christianity, block by block, by demonstrating the rationality of each discrete component of Christian theology. The engagement of a believer with an unbeliever thus starts on neutral ground and then seeks to establish each tenet of Christian belief separately by means of evidences and reason.

I would suggest that this represents an unwarranted misreading of Warfield’s words. Although Warfield did believe in the possibility of demonstrating God’s existence from nature, he did not place proofs of theism in a neutral territory, divorced from the rest of Christian faith. According to Warfield, Christian apologists must recognize their goal as the demonstration of the truth of “Christianity as a whole,” never succumbing to the “fatally dualistic conception which sets natural and revealed theology over against each other.” Christianity must never—for Warfield—be hewn into a series of utterly separated building blocks. “The details of Christianity are all contained in Christianity,” Warfield contended, “the minimum Christianity is just Christianity itself.”

When Warfield declared that apologetics lays “the foundations on which the temple of theology is built and by which the whole structure of theology is determined,” he was not presenting these foundations as a neutral territory where Christians and non-Christians meet on equal footing. Neither was he contending for what Van Til called “block house apologetics.” Warfield was identifying the theological starting point at which their engagement may begin—a point at which Christian revelation begins to be recognized and established as the truth. Certain truths may be more foundational and more accessible than others, but this does not mean that these truths have been subjected to human judgment or divorced from the whole fabric of Christian theology.

The purpose of apologetics was never, in Warfield’s thinking, to prove each individual tenet of Christianity by appealing to human reason or evidence. Such a requirement would, in Warfield’s words, “betray us into the devious devices of the old vulgar rationalism.” From Warfield’s perspective, apologetics was not so much a vindication as a demonstration. The goal of the apologist is not to prove the truth of Christianity; it is rather to demonstrate that Christianity is truth.

To be sure, Cornelius Van Til would still have disagreed with Warfield. Warfield did, after all, wish to begin his apologetic argument with theism instead of beginning with the whole of the Christian faith as the only coherent worldview and as the only means of rational predication. Warfield also saw natural revelation as a domain in which some knowledge of God is available by the same means both to believers and to unbelievers—another point with which Van Til would have taken issue. It is, however, neither fair nor honest to suggest that Warfield attempted to operate “in neutral territory with the non-believer” or that Warfield’s apologetic failed to present Christian faith as an indivisible whole.

Van Til and the Apologetics of Abraham Kuyper

Abraham Kuyper was far less optimistic than B.B. Warfield when it came to the value of apologetics. Whereas Warfield saw apologetics as foundational, Kuyper kept the purpose and potential of apologetics quite narrow, delimiting the scope of apologetics to demonstrating the inadequacies of non-Christian worldviews by proclaiming the perfect coherence of the Christian worldview. For Kuyper, apologetics does not deal with false teachings in the church; that’s the place of polemics. Neither can apologetics demonstrate the inadequacy of the worship of false gods; that is the role of elenctic theology, according to Kuyper. There is, in fact, little or no value in any apologetic that attempts to provide evidence to answer specific claims made by unbelievers in Kuyper’s view. Such apologetics have, according to Kuyper, “advanced us not one single step” in the struggle against modernism. For Kuyper, the only apologetic worth proclaiming is the entirety of the Christian worldview as the only reasonable means by which anyone can make sense of the world.

Much like Kuyper, Cornelius Van Til saw Christianity’s engagement with other perspectives as a clash in which the Christian worldview unmasks the incoherence and inconsistencies in every alternative perspective. Van Til also, however, differed from Kuyper on the place of apologetics; Van Til still believed it was possible for Christian apologists to start with particular facts in the universe—with any fact or rational predication in the universe, to be precise—and to make a case for the truth of Christianity. The case for Christianity that Van Til wished to make was not, however, one that followed along the lines of his caricature of Warfield’s apologetics. Van Til—unlike Warfield—contended that the case for Christianity must be made by showing how any truth that the non-Christian knows is dependent on the entirety of Christian faith to be rationally known and articulated.

Common Ground and Common Notions in Van Tilian Presuppositionalism

So is it true that Cornelius Van Til excluded the possibility of meaningful dialogue between the believer and the unbeliever? Did Van Til actually reject any common ground on which the Christian and the non-Christian might meet? If he didn’t, how is it that he declared in The Protestant Doctrine of Scripture that “all intelligible contact” between the believer and the unbeliever is impossible?

As I’ve already noted, Cornelius Van Til does seem in some contexts to have rejected the reality of any “common notions” shared by believers and unbelievers. At the same time, in other contexts, he clearly embraced such notions. In The Defense of the Faith, for example, he wrote that “all men have common notions about God.” Despite this declaration, Van Til argued elsewhere that apologists should “no longer make an appeal to ‘common notions’” (“My Credo”).

So is there a contradiction here in the thought of Cornelius Van Til? I don’t think so—but I also don’t fault anyone who sees a contradiction here, because Van Til assumed two distinct and separate types of “common notions” but he didn’t consistently articulate this distinction.

The key to understanding Cornelius Van Til is to recognize that he distinguished between

- ethical and epistemological common notions on the one hand, and,

- psychological and metaphysical common notions on the other hand.

The first of these, Van Til rejected when it comes to common ground between Christians and non-Christians; the second, he embraced.

In The Defense of the Faith, Van Til declared that the commonality of common notions between believers and unbelievers is limited to the psychological and metaphysical realms. Every human being lives with a psychological and metaphysical awareness that the God described in Scripture exists, according to Van Til; the difference between the Christian and the non-Christian is that the non-Christian suppresses this awareness. There is, however, no common notion that unites the Christian with the non-Christian when it comes to the basis of one’s reasoning (epistemology) or the rationale behind one’s moral life (ethics).

“Natural man has epistemologically nothing in common with the Christian,” but “all men have all things in common metaphysically and psychologically,” according to Van Til. That’s why, in his perspective, it is fully possible to appeal “to the ‘common ground’ which [Christians and non-Christians] actually have because man and his world are what Scripture says they are” (“My Credo”). This appeal can never, however, follow any common epistemological processes or foundations because the non-Christian’s epistemology is internally incoherent.

Non-Christians thus may “have all the facts in common with” Christians, but non-Christians arrive at these facts on the basis of an inconsistent epistemology which borrows from a Christian worldview while denying the truth of that worldview. And that is why there can be, for Van Til, “no single territory or dimension in which believers and non-believers have all things”—that is to say, not only their psychology and metaphysics but also their epistemology and ethics—“wholly in common.”

The epistemology of the non-Christian is incoherent and inconsistent—according to Van Til’s thinking—because only a Christian worldview is capable of explaining the world as it actually exists. Only a Christian worldview provides the necessary foundation for rational predication, because only the Christian worldview solves the problem of the One and the Many by means of the ontological Trinity. And so, if any person—Christian or non-Christian—knows any fact or rightly describes any phenomenon in the universe, that person does so by relying on a Christian worldview, even if she or he rejects this very worldview.

To put it another way, even if the Christian and the non-Christian arrive at the same conclusions, the foundation from which the nonbeliever thinks that she or he is reasoning has nothing in common with the basis on which the Christian has found knowledge and truth. Any similarities between Christian and non-Christian reasoning processes exist only because the non-Christian has borrowed unknowingly from a Christian worldview. Thus, Van Til is able to contend that “the natural man has epistemologically nothing in common with the Christian” (The Defense of the Faith). Non-Christians know truth but they delude themselves into thinking that they know these truths on some basis other than a Christian worldview. Christians know the same facts but Christians alone know why they know what they know.

Once we’ve understood this point, it finally becomes possible for us to answer the question of whether or not—from the perspective of Van Tilian presuppositionalism—the Christian and the non-Christian share any common notions. According to Van Til, there is total psychological and metaphysical common ground that unites all humanity. The believer and the non-believer may even hold all facts in common about a particular topic. From the standpoint of epistemology, however, believers and non-believers have nothing in common. That’s because the non-believer believes that he or she has somehow arrived at these facts without reference to the worldview that is presented in Scripture. And so, the Christian and the non-Christian have everything in common metaphysically but nothing in common epistemologically.

So did Cornelius Van Til reject “common ground” or exclude “the possibility of a dialogue with those outside the Christian faith,” as Alister McGrath suggests?

Not at all.

Van Til may have been right or he may have been wrong, but he never completely rejected the reality of common ground shared by believers and non-believers. What Van Til rejected was the possibility of any common epistemological starting-point or shared epistemological process on which Christians and non-Christians can agree. Whether correct or incorrect, Van Til’s system was internally consistent and coherent.

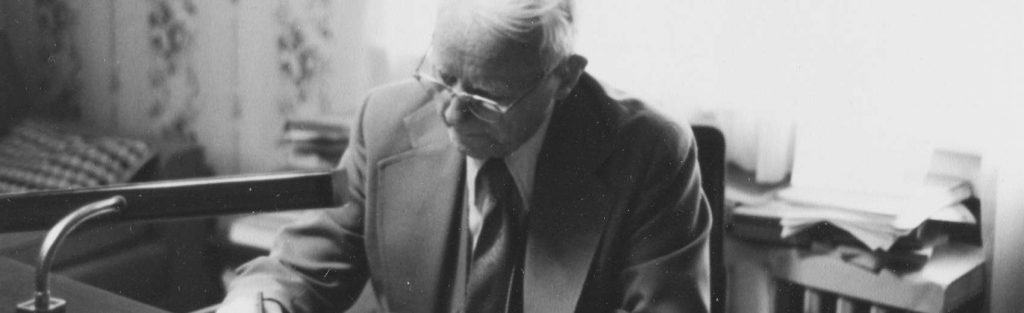

I, for one, would question the accuracy of Van Til’s separation between epistemological common notions and metaphysical common notions. This bifurcation does not seem to me to be faithful to the concept of common notions in the canons of Dordt. From the perspective of the pastors at the Synod of Dordt, epistemology and metaphysics seem to have been intertwined, and the resulting common notions were perceived as being limited to basic ethics and knowledge of God.

To put it another way, the limit in common notions is not one of type, in which the unbeliever has commonality in metaphysics but not epistemology; the limit is rather a limit of degree, in which metaphysics and epistemology are shared to a certain point but not beyond that point, apart from the regenerating work of the Holy Spirit. B.B. Warfield made much the same point in a different context when he pointed out that

the product of the intellection of these “two kinds of men” [regenerate and unregenerate] will certainly give us “two kinds of science.” But the difference between the two is … not accurately described as a difference in kind—gradus non mutant speciem. Sin has not destroyed or altered in its essential nature any one of man’s faculties, although—since it corrupts homo totus—it has affected the operation of them all. The depraved man neither thinks, nor feels, nor wills as he ought; and the products of his action as a scientific thinker cannot possibly escape the influence of this everywhere operative destructive power. … Nevertheless, there is question here of perfection of performance, rather than of kind.I would suggest that a limit of degree rather than type is more consistent with Scripture and with the church’s historic declarations of faith.

Additionally, neither Scripture nor the earliest Christian apologists make—or even seem to consider—Van Til’s claim that the ontological Trinity is necessary, whether consciously or unconsciously, for rational predication.

At the same time, it seems to me that one might still utilize some form of Van Til’s approach. Faced with a fact on which a believer and an unbeliever agree, the evidentialist would see this fact as a point of common ground and then try to build a case from this fact. The Van Tilian presuppositionalist would endeavor to show that this single fact can only be known and trusted if the entirety of the Christian worldview is also true. Faced with the same fact, a less rigid presuppositionalist—such as myself—might assert that this fact necessitates a theistic worldview and that Christianity is the best evidenced expression of theism. This is not to suggest a starting point that is in any way neutral. Any fact that can be known as true is known as true only in and through Jesus Christ in whom all of creation holds together. It is instead as an approach that takes care not to base too much on any single fact. In particular, it moves from Van Til’s reliance on the ontological Trinity to what I would consider to be a more biblically-grounded focus on the work of God in Christ in history.

I suspect that Cornelius Van Til would have been repulsed by my modification here and that he would have rejected it as a capitulation to the world’s way of thinking. So be it. I contend that what I have presented is more faithful not only to apologetics as practiced in Scripture but also to pre-medieval Christian apologists in particular and to the early Reformed confessions of faith. Evidence for Christian faith is an intricate web of interconnected truths scattered across the cosmos and throughout history. Taken in isolation, any one of these truths might have a multiplicity of explanations but, together, they reveal a beautifully reasonable and well-evidenced confession that’s centered in a bloody cross and an empty tomb.