With few exceptions, even the most skeptical scholars admit that Jesus was crucified—and with good reason. Not only the authors of the New Testament but also later Christian writers, the Roman historian Tacitus, and quite likely the Jewish historian Josephus mention the crucifixion of Jesus. And it’s highly unlikely that first-century Christians would have fabricated such a shameful fate for the founder of their faith. In the first century A.D., crucifixion represented the darkest possible path to death, after all.

In fact, it is almost impossible for contemporary people to comprehend the full obscenity of crucifixion in the ancient world.

Beginning as early as the third century B.C., the very word “crucify” was a vulgarism that did not pass freely between the lips of cultured people. In one ancient document, a Roman prostitute hurled this insult—perhaps the lewdest curse in her vocabulary—at an uncouth patron: “Go get yourself crucified!” The Roman philosopher Seneca described what he witnessed at a crucifixion with these words: “I see the stakes there—not of one kind but of many. Some victims are placed head down; some have spikes driven through their genitals; others have their arms stretched out on the gibbet.”

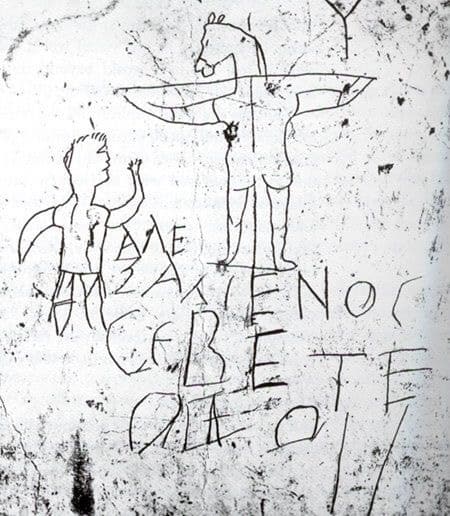

That’s why Romans referred to the Christians’ worship of a crucified God as “foolishness,” “insanity,” and “idiocy.”

What Happened to Corpses after Crucifixion?

The shame of crucifixion ran deeper than the nakedness, the torture, and taunting. In most cases, crucified bodies were not even buried. Instead, in the days that followed the deaths of the crucified, the beaks of vultures and the teeth of wild dogs frequently tore the corpses to shreds and scattered their remains across the countryside.

Roman crucifixion was state terrorism; its function was to deter resistance to revolt and the body was usually left on the cross to be consumed by wild beasts. … The norm was to let crucifieds rot on the cross or be cast aside for carrion.

According to some critics of the New Testament Gospels—John Dominic Crossan of the Jesus Seminar, for example—that’s what happened to Jesus too.

Consumed by birds and beasts, the flesh of Jesus degenerated inside the stomachs of wild creatures and became dung that decayed in the sun in the alleys of Judea.

Not a pleasant thought, is it?

Not the end that you’d imagined for someone as celebrated as Jesus.

So what if it’s true?

Such critics do have some archaeological and literary evidence that stands on their side. Not long after the birth of Jesus, the Roman general Varus crucified two thousand Jewish rebels at once. While besieging Jerusalem in A.D. 69 and 70, Titus the Roman general crucified Jewish captives in view of the denizens of Jerusalem. In each of these cases—and in many, many other instances of mass execution—the bodies seem to have remained on crosses. There, weather and wild creatures reduced their flesh to dust and dung. Suetonius wryly noted regarding a crucified man, “The carrion-birds will quickly take care of his burial.” “The vulture hurries,” the satirist Juvenal claimed, “from dead cattle to dead dogs to crosses.” The epitaph of a second-century murder victim includes this haunting clause: “My murderer was suspended from a tree, while still alive, for the benefit of beasts and birds.”

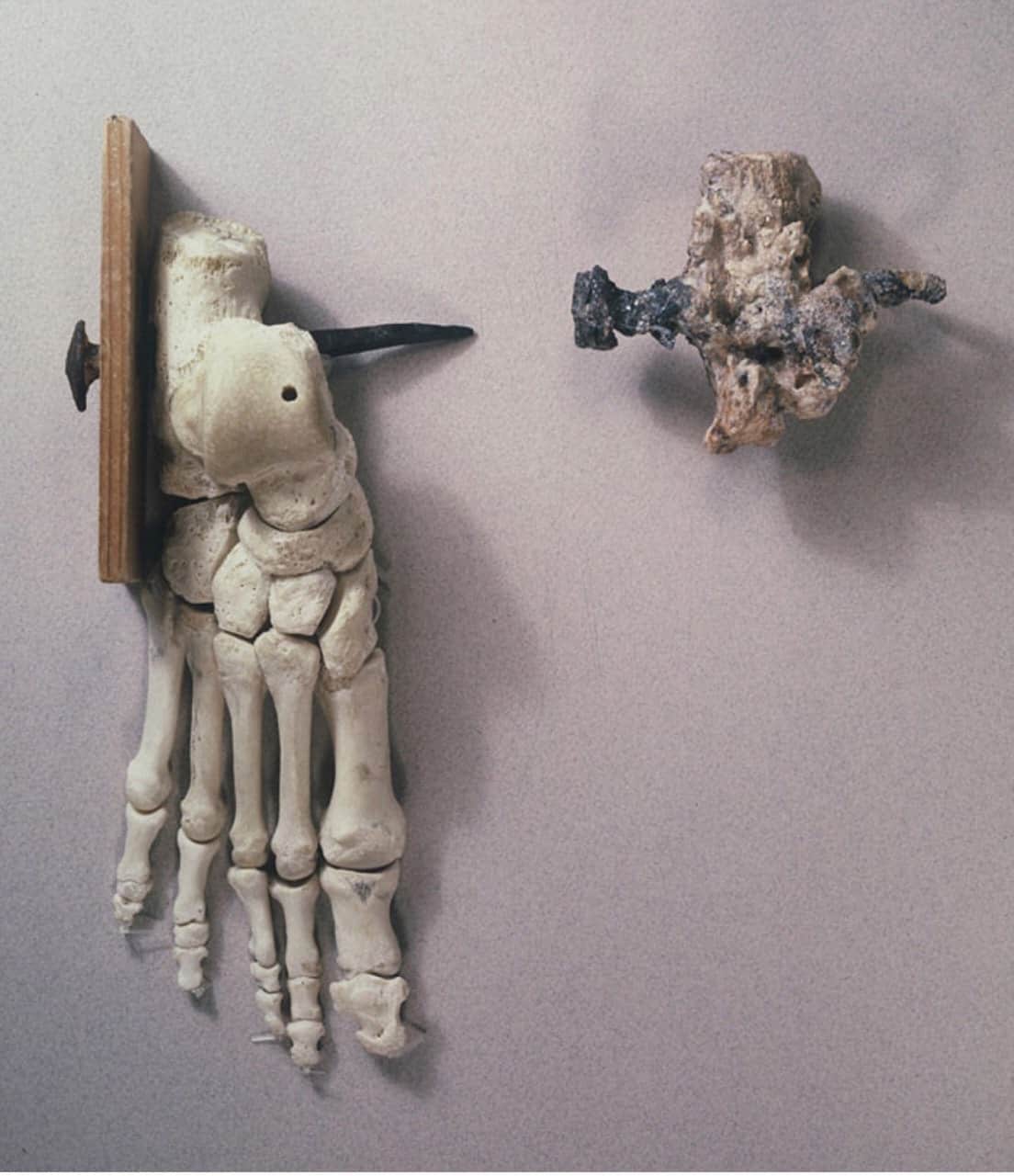

The critics have a bone that could support their argument too—a heelbone with a spike in it, to be exact. Over the span of four centuries, the Romans crucified tens of thousands of murderers, revolutionaries, and persons who happened to be trapped on the wrong side of the political tides. Yet the only fragment that has been found from these thousands of cadavers is one single heelbone, still pierced by a spike. According to the inscription on the side of this man’s ossuary, the man’s name was John; he was Jewish.

And why have the remains from only one crucified body survived? Well, according to some skeptics like John Dominic Crossan, it’s because, in nearly all cases, weather and wild creatures dealt with the corpses of the crucified. Crossan declares,

We have found only one body from all the thousands crucified around Jerusalem in that single century. I keep thinking of all those other thousands of Jews crucified around Jerusalem in that terrible first century from among whom we have found only one skeleton and one nail. … I think I know what happened to their bodies, and I have no reason to think Jesus’ body did not join them.

And what of the resurrection? From Crossan’s perspective, the resurrection was mere fiction—nothing more than a hallucination that emerged from the disciples’ deep-seated hopes and dreams that they might see Jesus again. If such critics have rightly reconstructed history, Good Friday was not good, and Resurrection Sunday was no triumph. Jesus died, his corpse remained on the cross, and the resurrection was nothing more than a series of hallucinations and fabrications.

So what really happened to the body of Jesus?

Is there any historical foundation for believing that the body of Jesus was entombed in the way that the New Testament Gospels claim?

Or could it be that Crossan and other critics are correct?

I am not convinced that historical nor literary artifacts provide any support for Crossan’s contention that the corpse of Jesus became carrion for dogs and birds. In fact, in the context of Jerusalem around A.D. 30, the best available evidence points in the precise opposite direction. Even if you disagree with me, please at least take a look with me at both sides of the evidence for the burial of Jesus’ crucified body.

The Religious Leaders Would Have Wanted the Body of Jesus Buried

In many areas of the Roman Empire, crucified bodies probably did become pickings for vultures and dogs—that much is certain.

But not always, and not everywhere.

In Judea—and especially around Jerusalem—there was a law that, from the perspective of the Jewish people, came from a higher source than Caesar. In this law, God commanded the Israelites: “If someone commits a capital crime for which he is executed and if you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night upon the tree. You shall bury him the same day, for anyone hanged from a tree is condemned by God. You shall not defile your land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance” (Deuteronomy 21:22-23; see also Ezekiel 39:14-16).

The Temple Scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran testifies to how seriously Jews took this command even during the times of exile and occupation: “You shall not allow bodies to remain on a tree overnight; most assuredly, you shall bury them, even on the very day of their death.” The Jewish book of Tobit—an entertaining little text, penned in the time-period that stands between the Old and New Testaments—identifies the burial of abandoned corpses as an act of supreme piety. Near the end of the first century A.D., the Jewish historian Josephus contrasted the Jewish perspective on crucified bodies to typical Roman practices. According to Josephus, “Jews are conscientious about their burial practices—so much so that even criminals sentenced to crucifixion are removed and buried before the sun sets!” In another writing, Josephus stated, “[Jews] must furnish fire, water, and food to anyone who asks, giving directions to the right road, never leaving a corpse unburied.” Later rabbis echoed this concern for the deceased.

Especially approaching a festival as important as Passover, the Jewish people and particularly the religious leaders would have wanted the body of Jesus removed from the cross. And, in the case of a figure as popular and potentially problematic as Jesus, it’s likely that someone would have been willing to bury him—even if that act rendered the person ceremonially unclean.

In this context, the request of Joseph of Arimathea makes complete sense (Mark 15:43-45). To be sure, Joseph wanted to honor the body of Jesus. But, from the perspective of Pontius Pilate and fellow members of the ruling council, here’s how his motive would have appeared: As a member of the ruling council, Joseph of Arimathea wanted the corpse removed before sundown to avoid any defilement in the land of Israel (Deuteronomy 21:23). A burial overseen by the Jewish ruling council also fits with Papyrus Cairo 10759—a fragmentary account of the life of Jesus that, though written several decades after the apostolic eyewitnesses, retains remnants of an ancient retelling of the resurrection narrative, independent of the New Testament Gospels.

Someone would have wanted to bury the body of Jesus—that much seems certain. Both the Roman authorities and the ruling council would have wanted to stifle any loyalty to this would-be Messiah as soon as possible. Furthermore, from a Jewish perspective, not to bury his body would have violated the law of God. So, the question isn’t whether anyone would have requested the body of Jesus—someone would have. The question is, “Would the Romans actually have granted such a request?” The answer to that question is clearly yes.

Pontius Pilate Would Have Handed Over the Body of Jesus for Burial

But Jesus wasn’t crucified in a time of war.

He was, in fact, crucified during a relatively peaceful period in the history of Judea.

And, in times of relative peace, Romans consistently respected the laws of occupied nations. “The Romans,” Josephus contended, “do not require … their subjects to violate their national laws.”

As part of this pattern of toleration for local peculiarities, Pontius Pilate would have granted the body of a deceased Jew to his own people—even if Roman law didn’t demand it. After all, hadn’t Herod Antipas given the body of John the Baptist to his disciples after he beheaded the popular prophet? During a potentially volatile religious festival, Pilate would have had an even greater reason to respect local customs. Pilate’s desperate determination to maintain peace during the Passover would probably have persuaded the governor to hand over the body of Jesus for burial.

But such concessions weren’t merely Roman practice.

They were Roman law.

Here’s what the Pandectae—a summary of the Roman legal code—declared about the bodies of crucified criminals:

The bodies of those who are condemned to death should not be refused their relatives; and [Caesar] Augustus the Divine, in the tenth book of his Vita, said that this rule had been observed. … At present, the bodies of those who have been punished are only buried when this has been requested and permission granted; and sometimes it is not permitted, especially where persons have been convicted of high treason. … The bodies of persons who have been punished should be given to whoever requests them for the purpose of burial.

This fits perfectly with the description in the New Testament Gospels. Roman practice required Pilate to provide the body of Jesus “to whoever” requested it “for the purpose of burial.” When Joseph of Arimathea requested the body of Jesus, Pilate verified that Jesus was dead—he had already dealt with Jesus once, and he didn’t want to deal with him again if he wasn’t quite dead and his followers somehow resuscitated him. Once a centurion confirmed that Jesus was dead, Pilate granted Joseph’s request.

“Roman legal practice,” Gerd Lüdemann claims in the book What Really Happened?: A Historical Approach to the Resurrection, “provided for someone who died on the cross to rot there or be consumed by vultures, jackals or other animals.” Despite the confident title of Lüdemann’s text, this was not “what really happened” at all; in fact, Roman legal practice provided for the precise opposite of this claim. Other than mass crucifixions during times of war or revolt, it was when a Roman citizen was executed for high treason that burial was forbidden—a category that the crucifixion of Jesus certainly didn’t fit. Jesus of Nazareth was not a Roman citizen, and he hadn’t conspired against Caesar.

Why Were So Many Bodies Left on the Crosses?

So, why—if families could request an executed corpse—does Roman literature include so many references to the consumption of crucified corpses by birds and beasts? And why has only a single heelbone from one crucified man ever been found?

So, why—if families could request an executed corpse—does Roman literature include so many references to the consumption of crucified corpses by birds and beasts? And why has only a single heelbone from one crucified man ever been found?

Don’t forget this crucial fact: Crucifixion constituted a supreme dishonor in the ancient world. The very word “crucify” remained unmentioned in polite company. Among Romans, suicide was to be preferred above a cross. As such, beyond the borders of the Jewish provinces, it would have been highly unusual for a family to reclaim the corpse of their crucified kin; families would have disowned this person because of the shame that the accused criminal’s actions had brought on their family’s name.

These forsaken bodies—the vast majority of the victims of Roman crucifixion—remained on their crosses to be consumed. Thus their remains disintegrated into the dust of the Roman Empire. But the case of Jesus—a Jew, crucified near Jerusalem on the eve of a popular religious festival—doesn’t fit this pattern. The Jews would have wanted Jesus buried, and Roman practice called for Pontius Pilate to grant this request.

If you’re interested in learning more about the historical impact of Christianity, take a look at the book and video series Christian History Made Easy. To learn how to respond to critics of the reliability of the New Testament Gospels, consider reading Misquoting Truth.

How should the obscenity of the crucifixion shape the way that the message of Jesus is proclaimed on Good Friday and on Resurrection Sunday?

SOURCES: 11QT64:11-13; 11QT48:10–14; 4Q524; Craig Evans, “Jewish Burial Traditions and the Resurrection of Jesus”: http://www.craigevans.com; N. Haas, “Anthropological Observations on the Skeletal Remains from Giv‘at ha-Mivtar,” Israel Exploration Journal 20 (1970) 38–59; Martin Hengel, Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross rev. ed. (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1977); Josephus, Antiquitates Judaica, 17:10; 18:5; Bellicum Judaicum, ed. H. St.-J. Thackeray, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927) 2:5; 4:5; 5:6-11; Contra Apionem, in The Life, Against Apion, ed. H. St.-J. Thackeray, in Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1926) 2:6, 29; Juvenal, Satires, 14:77-78; S. R. Llewelyn, ed., New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity, vol. 8 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998) 1; Mishnah Sanhedrin 6:4-6; Philo of Alexandria, In Flaccus, Philo, ed. F.H. Colson, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1941) 10:81-85; Seneca, De consolatione ad Marciam, in Volume II: Moral Essays, ed. John Basore, in Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1932) 20:3; Cornelius Tacitus, Annales, 6:29; 15:44; Tobit 1:18–20; 2:3–8; 4:3–4; 6:15; 14:10–13; V. Tzaferis, “Crucifixion–The Archaeological Evidence: Remains of a Jewish Victim of Crucifixion Found in Jerusalem,” Biblical Archaeology Review 11 (January—February 1985): 44-53.