On October 6, 1536, William Tyndale was burned at the stake. He was only forty-two years old or so at the time, but the work he had already accomplished in those four decades of life would change the world. You’ve probably seen the bumper sticker: “If you can read, thank a teacher.” Another bumper sticker—or Bible sticker, perhaps—would be every bit as appropriate: “If you can read the Bible in English, thank William Tyndale.”

After graduating from Oxford University and studying at Cambridge University, William Tyndale became a chaplain and tutor for a wealthy family. One evening, a visiting priest challenged Tyndale’s interpretation of a difficult text. During the debate, the priest declared his perspective on the value of Scripture.

“We had better be without God’s law than the pope’s,” the priest said—in other words, “It would be better to be without God’s law than to be without the pope’s law.”

“If God spares my life,” William Tyndale retorted, “I will cause a boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scripture than you do.”

This goal—to make Scripture accessible to everyone in England—became William Tyndale’s driving passion. He requested permission to translate the Greek New Testament into English, but his bishop rejected his request. Tyndale fled to the German provinces and began translating the Scriptures anyway.

How Tyndale’s Translation Reshaped the English Language

Nearly every English Bible translation throughout the past half-millennium has been influenced somehow by this work from William Tyndale. In fact, without Tyndale’s translation of the Bible, the English language itself wouldn’t be the same! Tyndale’s translations coined dozens of now-common words—terms like “fisherman,” “seashore,” and “scapegoat” as well as the modern usage of “beautiful.”

But then Tyndale ended up on the wrong side of the king.

How Tyndale’s Dying Prayer Changed the World

In 1530, William Tyndale published a little tract entitled Practice of Prelytes. This tract denounced the annulment of the Henry’s wedding vows and landed Tyndale on the list of England’s most-wanted outlaws. The next year, King Henry VIII issued an edict declaring “the translation of Scripture corrupted by William Tyndale … should be utterly expelled, rejected, and put away.” Tyndale’s translation was one of the greatest masterpieces ever produced in the English language—and yet, one of the many charges brought against him was that he had produced a “corrupted” English Bible!

One day in 1535, a smooth-talking Englishman named Henry Phillips showed up on Tyndale’s doorstep, pretending to support reform in the churches. He gained Tyndale’s trust and then betrayed him into the hands of imperial authorities. For more than a year, William Tyndale suffered in a castle dungeon near Brussels, still determined to finish translating the Old Testament. One day in early October 1536, Tyndale was taken from his cell and tied to a post. As branches were piled around his feet, he cried out in a loud voice, “Lord! Open the king of England’s eyes!” Moments later, William Tyndale was strangled to death, and his body was set on fire.

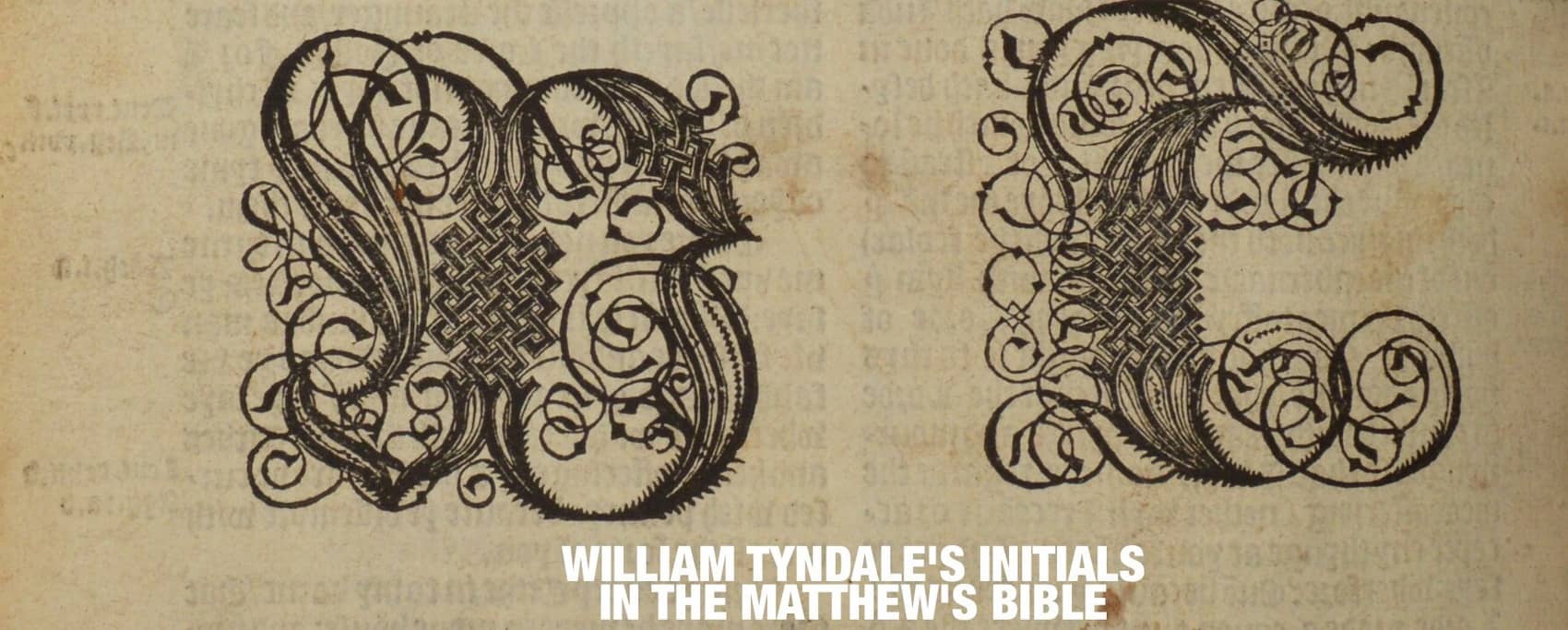

The next year, God answered Tyndale’s dying plea. King Henry VIII approved the Matthew’s Version of the Bible. What the king didn’t know was that “Matthew” was a pseudonym. A friend of Tyndale’s used the false name “Thomas Matthew” to disguise the fact that this Bible was mostly the work of William Tyndale. The letters “WT” were printed between the Old and New Testaments as a covert tribute to Tyndale’s contribution.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of the English Bible, take a look at the book and video series How We Got the Bible.

Watch the video about William Tyndale and the English Reformation. Even if you’ve never read Tyndale’s translation of the Bible, at least two-thirds of the King James Version is drawn from the work of William Tyndale, and the verbiage of King James Version still shapes the wording of Bible translations today. How did this article and video help you to understand and to appreciate the contributions of William Tyndale? What did you learn that you didn’t know before? What questions do you still have about William Tyndale?