Today, St. Nicholas is mostly known as a paunchy old geezer who spends one night each year breaking into people’s houses and stealing cookies before escaping to an Arctic hideaway where enslaved elves do his work for him.

Kind of creepy when you think about it.

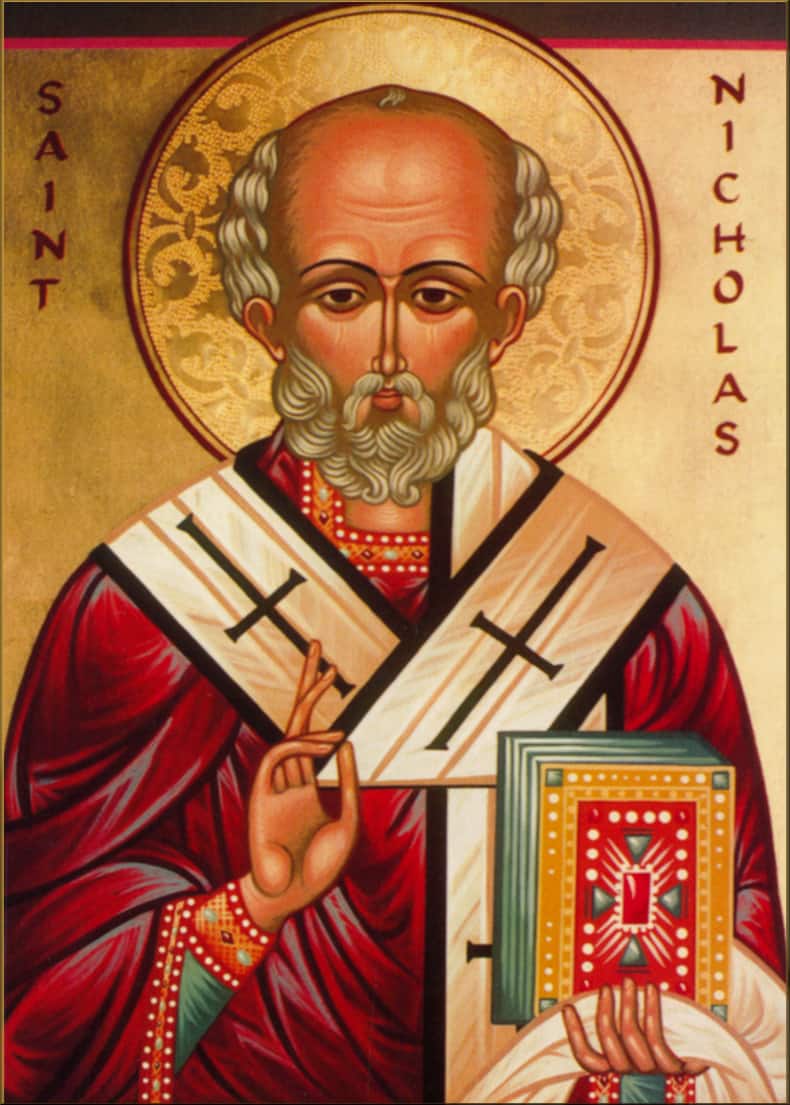

The good news is that none of this was what the real St. Nicholas—a church leader named Nicholas of Myra—was known for.

The story of the real St. Nicholas won’t make any sense until you understand what was happening in the Roman Empire in the late third and early fourth centuries. So, before learning more about Nicholas of Myra, let’s take a quick look at three emperors, a Great Persecution, and a vision of a cross.

:: Two Emperors and a Great Persecution ::

In 284, Diocletian became emperor of the Roman Empire. Early in his reign, Emperor Diocletian had a great idea: How about figuring out a way to transition from one emperor to the next without murdering the existing emperor? (If I ever become an emperor, I think I might just make this idea part of my party platform too.)

To accomplish this feat, Diocletian organized the empire into two parts, east and west. Each half had its own emperor and junior emperor so that the supreme emperor could retire and be replaced by some means other than violent death. This was a promising move on Diocletian’s part. There was something else promising about Diocletian as well: His wife and daughter were Christians, so many Christians thought that Diocletian’s reign would bring centuries of persecution to an end.

The Christians couldn’t have been more wrong.

Diocletian’s junior emperor was a man named Galerius, and Galerius was convinced that Christians were dangerous. After a fire in the imperial palace, Galerius goaded Diocletian into blaming and persecuting Christians. The result was the most violent outbreak of persecution that Christians had ever seen.

To gain a glimpse of what happened during those years of tribulation, read this account from the Great Persecution, written by an ancient Christian historian who lived during this time of terror: “Of Those in Egypt”

When Diocletian retired, Galerius continued his violent rampage against the churches. Then, in the year 311, a grotesque illness struck Galerius. Perhaps hoping for healing from the Christian God, Galerius legalized Christianity. Five days later, Galerius died. The new ruler who emerged in the ensuing chaos was a young man named Constantine.

:: Constantine’s Vision and Arius’s Heresy ::

The night before a decisive battle for the city of Rome, Constantine allegedly had a vision that included a cross and the words “In this, conquer.” He chalked a Christian symbol on his soldiers’ shields, credited the God of the Christians for his victory, and began favoring Christians. One year later, in a decree that would become known as “the Edict of Milan,” Constantine reiterated Galerius’s legalization of Christianity.

A few years later, when an Alexandrian elder named Arius caused division in the churches by claiming that Jesus was a created being, the emperor became even more involved in the business of the churches. Emperor Constantine convened the first church-wide council in the little village of Nicaea. More than three hundred Christian leaders from throughout the empire gathered at Nicaea to consider Arius’s claims.

Even though Constantine’s primary concern was not doctrinal purity but imperial unity, the church leaders at Nicaea rejected Arius’s false teachings with a beautiful, biblical summary of the church’s beliefs about Jesus; this summary would become known as the Creed of Nicaea. A later council—the Council of Constantinople—would develop this creed into the Nicene Creed that’s still recited today by millions of Christians throughout the world.

Historians disagree when it comes to Constantine’s conversion. Some see him as a courageous convert to the Christian faith. Others think that Constantine never actually understood the gospel and, because Constantine shackled Christianity to the power of the state, he damaged the church’s witness for the next thousand years plus.

My take is somewhere between these two perspectives, but I’m a lot closer to the second perspective than to the first. Constantine wasn’t simply claiming Jesus for political reasons—his acceptance of Christianity was too risky to be a well-calculated political move. At the same time, even though Constantine seems to have sincere in what he claimed, he was not a Christian by any definition of “Christian” that I can possibly articulate from the New Testament, and his impact on Christian history has been far more negative than positive.

To learn more about Constantine, take a look at this article: Constantine the Great.

:: Black Dwarf, Santa Claus, and the Brawl at Nicaea ::

One man who was known to have been at the Council of Nicaea was a short dark-skinned deacon named Athanasius. After the council, Athanasius became the leading pastor in Alexandria, Egypt, as well as one of the most important fourth-century defenders of Nicene orthodoxy.

Learn more about “the Black Dwarf” by reading this article: Athanasius of Alexandria.

According to some reports, another famous church leader attended the Council of Nicaea too: Nicholas of Myra. That’s right, Santa Claus may well have been present when more than three hundred church leaders rejected the claim of Arius that “there was a point when the Son did not exist”!

And he may even have voted against Arius’s claims with something a bit stronger than his voice.

Learn more about Nicholas of Myra and the Council of Nicaea by watching this: “The Real St. Nicholas”

30 Days through Church History: Day 10