Every human being is hungry for a single overarching storyline that ties all of our smaller stories together. Since 2008, evidence for this hunger has been as close as your nearest cinema. That’s when the release of Iron Man marked the genesis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is not merely a series of movies, neatly sequentialized into episodes that convey a single storyline. The MCU includes a multiplicity of individual narratives. Taken together, these storylines form a master narrative—a metanarrative—that turns out to be as vast as the universe itself.

The Marvelous Metanarrative of the Marvel Cinematic Universe

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has been organized into three phases. When finished, these phases will span more than twenty total films that unfold over twelve years.

- Marvel Cinematic Universe Phase 1 (2008-2012): Over the course of six films, the heroes are introduced and—in the sixth film—brought together to form the Avengers.

- Marvel Cinematic Universe Phase 2 (2013-2015): Through six more films, it becomes clear that the battles the Avengers are facing are part of a far larger and more villainous scheme than anyone knew at the beginning.

- Marvel Cinematic Universe Phase 3 (2016-2020): The Avengers become fragmented before reuniting to keep the Infinity Stones from being used to control the universe.

This intertwining avalanche of films has already earned more than ten billion dollars, suggesting that the notion of many stories entwined in a single metanarrative has captured the attention of more than a few moviegoers. One reporter has even argued that “comics are the new Bible,” complete with warring gods and conflicting canons.

The Longing that Nature Alone Cannot Explain

This fascination with an overarching metanarrative shouldn’t surprise us.

Humans are, after all, ever and always seeking some sort of metanarrative to make sense of our lives. “Man is,” Alasdair MacIntyre has written, “in his actions and practice, as well as in his fictions, essentially a story-telling animal.” English professor Jonathan Gottschall echoes, “Neverland is our evolutionary niche, our special habitat.” For human beings, “the normative is”—in the words of sociologist Christian Smith—“organized by the narrative.” We are homo narrans—creatures who create and who are created by narratives.

Naturalistic theorists see this thirst for narrative as an evolutionary adaptation that enables human beings to cope with challenges by formulating frameworks of meaning that make sense of our lives. Natural selection alone, however, cannot account for the stories we tell. That’s why we as believers in Jesus Christ seek a deeper reality, hidden beneath the surface of humanity’s passion for narrative.

Deep inside, every human being knows that the cosmos is constituted by far more than a naturalistic continuum of randomly-generated causes and effects. The universe is a theater of divine glory, and the story that is being performed in this theater is pregnant with meaning and purpose. Regardless of what our mouths may declare, our hearts know that the little stories of our lives are being woven into a majestic metanarrative with an endpoint that was known to God before time began. Seen in this way, perhaps these intricately intertwined stories of superheroes have multiplied in popularity because they provide a fleeting glimpse of a supernatural metanarrative in an increasingly secularized world.

A Metanarrative More Marvelous than Marvel

At the center of God’s more marvelous metanarrative stands this singular act: In Jesus Christ, God personally intersected human history and redeemed humanity at a particular time in a particular place. Yet this central act of redemption does not stand alone. It is bordered by God’s good creation and humanity’s fall into sin on the one hand and by the future consummation of God’s kingdom on the other. Long before the Marvel Cinematic Universe organized its metanarrative into three phases, Christian theologians have been organizing this metanarrative into four phases:

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 1: Creation: God created the cosmos and positioned Adam and Eve as vice-gerents (Genesis 1:26-31). By forbidding them to eat of one tree, God demonstrated that he remained sovereign over his world (Genesis 2:15-16).

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 2: Fall and Law: Humanity rebelled and refused to submit themselves willingly to their Lord and King. God exiled the first humans from paradise and revealed a plan to redeem humanity through the offspring of Eve (Genesis 3:15-24).

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 3: Redemption: Through Jesus the righteous King and divine Son, God broke the curse that resulted from humanity’s rebellion (Galatians 3:10-14). Through his resurrection on the third day, Jesus demonstrated his triumph over death and sin (1 Corinthians 15:20-28).

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 4: New Creation: In his own time and way, God will consummate the reign that Jesus Christ inaugurated through his life, death, and resurrection. God himself will dwell among his people and make all things new (Revelation 21:1-5).

This four-phase metanarrative of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation is the story that Christians have repeated to one another and to the world ever since Jesus left this planet through a gash in the eastern sky and sent his Spirit to dwell in his people’s lives.

Seeing Our Myths through the Lens of God’s Metanarrative

This more marvelous metanarrative provides us with a framework for how we view the world around us—including the films that we flock to theaters to see. Humanity’s best stories are, after all, always stolen from God’s greater story. “Every artist is a cannibal, and every poet is a thief,” Bono once sang, and he spoke more truth than he knew. Humanity’s finest artistic moments always turn out to be fregiments and echoes stolen from God’s greater metanarrative, momentary glimmers of light that reveal the story of God in spite of themselves. They are signposts that have been borrowed from our Creator’s storyline and reshaped to elicit within us a longing for a narrative that’s greater than ourselves. J.R.R. Tolkien said it this way:

We have come from God…[so] inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Myths may be misguided, but they steer us, however shakily, toward the true harbor.

The primary purpose of the human myths is to point us toward the beauty of the great story of God. If we fail to see that these myths are meant to point us to something greater, they will—in the words of C.S. Lewis—“betray us. … [For] they are not the thing itself; they are the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have never heard.”

But how can we learn to glimpse the story of God in the best of human myths?

One way is to use God’s metanarrative as a lens for thinking about the stories we read in books and see on the silver screen. Here’s a framework that I frequently use with my family to talk about the films we watch:

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 1: Creation: What did you see in this movie that reflected God’s good and beautiful design? God did not merely create a universe that works; he created a universe that’s beautiful, and he created human beings with the capacity to appreciate and to create beauty. Where did you glimpse that beauty in this film? Does this movie present us with the dream of a glorious past that’s been lost? If so, what did that past look like? How was this glorious past similar to or different from Eden?

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 2: Fall and Law: What in this movie was inappropriate and unworthy of imitation? What were the makers of this movie trying to tell us that is false or only partly true? What is broken in this movie that the heroes are trying to redeem or to repair?

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 3: Redemption: What does this movie present as the answer to the brokenness that drives the plot? How do the heroes redeem or repair the brokenness in this movie? Was there a willing act of sacrifice followed by resurrection or redemption?

- God’s Metanarrative Phase 4: New Creation: What is this movie’s vision for the way life ought to be? What is the hero’s hope for the future? What does the movie leave you longing for? What desires for the future did this movie awaken within you?

Every human being is hungry for a metanarrative because God has created us for metanarrative. The narratives that we see in the best of books and films are momentary hints of God’s more marvelous metanarrative. Seen in light of this greater story, these smaller storylines are tools that teach us to see the glory of God’s common grace in every time and space and place.

What’s your favorite film so far in the Marvel Cinematic Universe? Which one is your least favorite? Which films fit most clearly in the four-phase metanarrative of Scripture? Where in these films do you glimpse a clear sense that redemption requires a willing sacrifice followed by resurrection?

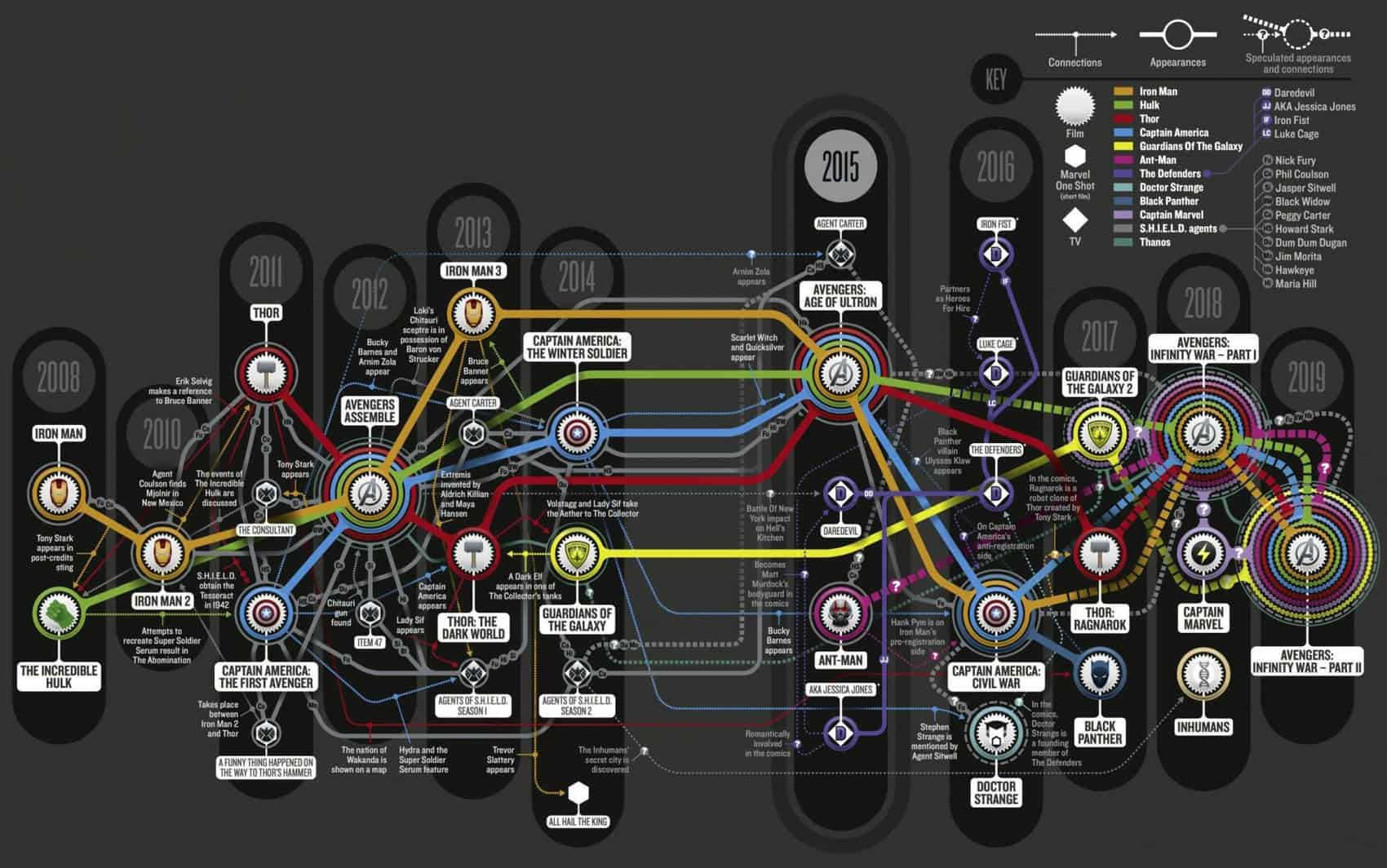

The MCU graphics in this post are not my own and are the property of their creators.