I need your help! Here’s the challenge: I’m working on a video that summarizes the history of the Bible in six minutes. Below, I’ve posted the script so far—and I’d be interested to know what you think needs to be included and what might be left out. The narration for the video is already six minutes long, so nothing can be added without taking something out. What that means is that, if you suggest any additions, you’ll need to point out some possible deletions as well!

I need your help! Here’s the challenge: I’m working on a video that summarizes the history of the Bible in six minutes. Below, I’ve posted the script so far—and I’d be interested to know what you think needs to be included and what might be left out. The narration for the video is already six minutes long, so nothing can be added without taking something out. What that means is that, if you suggest any additions, you’ll need to point out some possible deletions as well!

_____

The Bible.

A perfect treasure of divine instruction.

Sixty-six books, two testaments, more than forty authors who together tell the story of the glory of God revealed in Jesus Christ.

The Bible.

God’s written revelation of himself, known in the mind of God before time began.

But how? How did these words make it from the mind of God to the minds of human beings and then to the book that we hold in our hands today?

According to the apostle Peter, people “spoke from God as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.” According to Paul, not merely the authors but the text itself was inspired, “breathed out by God.”

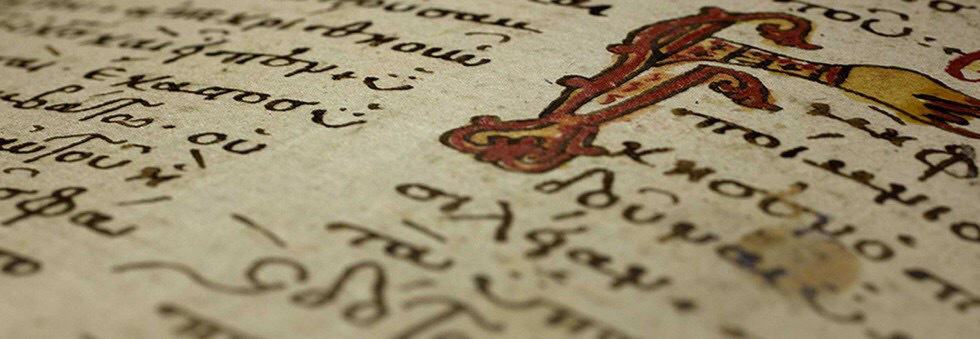

The first report we have of God calling a human being to write was on Mount Sinai, when God commanded Moses to write what he heard. And so, Moses recounted the story of God’s work with humanity all the way from the beginning of time up to the people’s entrance into the Promised Land. After the time of Moses, God superintended the lives of prophets and priests, poets and kings, so that they wrote the very words that God intended. They wrote on stone, on leather, on papyrus, in Hebrew and in Aramaic. As their proclamations and. prophecies turned out to be true, the people received their words as the very words of God.

Because they viewed these words as the words of God, the people of Israel wanted to preserve these words. In the early stages of Israel’s history, scribes carefully copied the books of the Old Testament. In the centuries that followed the time of Jesus, a group known as the Masoretes developed careful rules for the copying of scrolls—counting every letter of the Old Testament and including special markings to preserve the right readings of every text. When the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the twentieth century, scholars suddenly had access to Old Testament manuscripts that were hundreds of years older than the oldest text that the Masoretes had preserved. When these older texts were compared with the Masoretic Text, it became clear that—even though there were differences among these manuscripts—the process used by the Masoretes was a trustworthy process that reliably preserved the text of the Old Testament.

Because they viewed these words as the words of God, the people of Israel wanted to preserve these words. In the early stages of Israel’s history, scribes carefully copied the books of the Old Testament. In the centuries that followed the time of Jesus, a group known as the Masoretes developed careful rules for the copying of scrolls—counting every letter of the Old Testament and including special markings to preserve the right readings of every text. When the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the twentieth century, scholars suddenly had access to Old Testament manuscripts that were hundreds of years older than the oldest text that the Masoretes had preserved. When these older texts were compared with the Masoretic Text, it became clear that—even though there were differences among these manuscripts—the process used by the Masoretes was a trustworthy process that reliably preserved the text of the Old Testament.

When the last Old Testament prophet wrote his last inspired words, God’s written revelation came to an end—for a time. This silence didn’t last for a few months or a few years or even a few decades.

When the last Old Testament prophet wrote his last inspired words, God’s written revelation came to an end—for a time. This silence didn’t last for a few months or a few years or even a few decades.

It lasted four hundred years.

But God’s story was far from over.

The purpose of God’s work in the Old Testament had been to prepare the way for the coming of a Savior who would keep the covenants that Israel had broken. Every word of the Old Testament leans forward with eager anticipation in the direction of this Messiah. Those years of silence didn’t point to a failure in God’s plan; they were God’s preparation for the fulfillment of his plan.

And so, four centuries after God’s message was last written down, God spoke again.

These words that God spoke after those years of silence pointed to the coming of Jesus, the true and living Word of God. Jesus never criticized or corrected the Jewish Scriptures. Instead, he fulfilled them and treated them as the true and trustworthy words of his heavenly Father. And then, when he rose from the dead, Jesus demonstrated once and for all that his claims about himself and about the Scriptures were true.

After Jesus ascended into the heavens, those who had walked and talked with him passed on his teachings and the stories of his life—first in oral histories, then in literary productions recorded in the Greek language.

From the moment that words about Jesus began to be written, Christians received the words of eyewitnesses who had seen the risen Lord Jesus—as well as close associates of these eyewitnesses—as the authoritative words of God. Even in the first century, the apostle Peter treated the letters of Paul and words of the Old Testament as equal in their authority, and he referred to them both as “Scripture.”

Despite what many skeptics claim, the writings that became part of the New Testament weren’t chosen by any powerful bishop or emperor or church council. They were received as God’s Word because they were the trustworthy testimony of people who had either seen Jesus alive or were closely connected to those who had seen Jesus. Around twenty books of the New Testament were recognized as authoritative from the very beginnings of the Christian faith—and these included the Gospels and Acts, Paul’s letters and at least one of John’s letters. It took time for some of the others to become widely recognized in the churches—but, in the end, each of the 27 books of the New Testament was reliably connected back to an eyewitness of the risen Lord or a close associate of an eyewitness of Jesus. In time, these writings became known as “the New Testament”; together with the Old Testament, they are received by Christians as the words of God himself.

Despite what many skeptics claim, the writings that became part of the New Testament weren’t chosen by any powerful bishop or emperor or church council. They were received as God’s Word because they were the trustworthy testimony of people who had either seen Jesus alive or were closely connected to those who had seen Jesus. Around twenty books of the New Testament were recognized as authoritative from the very beginnings of the Christian faith—and these included the Gospels and Acts, Paul’s letters and at least one of John’s letters. It took time for some of the others to become widely recognized in the churches—but, in the end, each of the 27 books of the New Testament was reliably connected back to an eyewitness of the risen Lord or a close associate of an eyewitness of Jesus. In time, these writings became known as “the New Testament”; together with the Old Testament, they are received by Christians as the words of God himself.

Today, fragments, portions, or complete copies of more than 5,600 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament survive; differences do exist among these manuscripts, and yet the degree of agreement between them is overwhelmingly strong. Most important, not one of the many differences in these manuscripts affects any essential belief that we hold about Jesus Christ or about God’s work in the world.

The Bible—the Word of God preserved for us, a perfect treasure of divine instruction that testifies on every page to the glory of God in Christ.

_____

Discuss in the Comments:

What’s missing in this summary of the history of the Bible that needs to be added? What might be removed without diminishing faithfulness to the facts of history or essential tenets of evangelical theology?