Have you ever wondered how the Bible got started in the first place? That is one of the many questions I address in my new book How We Got the Bible. See the excerpt below from chapter two, “How Did the Old Testament Get from God to You?” to learn how the Bible began and who the first authors were.

How the Bible Began

The first writer of Scripture may well have been God himself.

One of the earliest mentions of written revelation in Scripture was when “the finger of God” etched the Ten Commandments on “tablets of stone” (Exodus 31:18; 32:15–16). Of course, God is a spirit; so, God doesn’t possess physical fingers and nails that scratched words into stone! (John 4:24). When Moses wrote that “the finger of God” etched the first edition of the Ten Commandments, he was using human imagery to identify the writer of these commands as God himself.

Unfortunately, Moses threw a temper tantrum shortly afterward and shattered those original stones (which is a bit of a shame since first-edition tablets from the hand of God would have been quite the collector’s item). After Moses got a grip on his temper, God issued a second edition of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 34:1). Moses put these tablets in the ark of the covenant (Deuteronomy 10:5)—but then, sometime in the sixth century BC, the Israelites ended up losing track of the ark. Today, as everyone who’s watched the Indiana Jones films knows, the ark resides in a top-secret United States government warehouse somewhere in Nevada. No, not really. Truth be told, no one knows what happened to the ark or the tablets. Some ancient Jews claimed the prophet Jeremiah hid the ark before the temple was destroyed; others said the ark was lost in Babylon.[1] Either way, no living human knows where those God-carved tablets ended up.

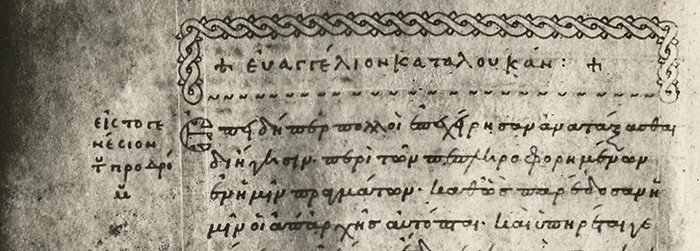

And so, God himself seems to have been one of the first authors of Scripture. But who was the first human to write Scripture? As far as we know from Scripture, that distinction belongs to Moses. It was Moses who kept records of Israel’s early wars, preserved “the words of the Lord,” and provided the Israelites with a “Book of the Covenant” (Exodus 17:14; 24:4, 7). Over time, Moses molded the texts that became the first five books of the Bible. Just like Luke who stitched many sources together to compose his Gospel (Luke 1:1–2), Moses most likely drew from a broad range of earlier materials to develop the Torah. Some of these sources originated with Moses, but many materials were probably passed down as oral traditions or fragments of text. Moses even cited one of his sources—“the Book of the Wars of the Lord”—by name (Numbers 21:14–15).

Who Wrote the Old Testament?

In the millennium that followed the life of Moses, other prophets along with priests and kings continued to record revelation “as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1:21). Historical books drew from court records, military reports, personal recollections, and oral traditions (see, for examples, 1 Kings 11:41; 14:19, 29; 15:7, 31; 16:5, 14, 20, 27; 22:45; 2 Kings 8:23; 12:19). King David wrote many of the psalms, and the wisdom of his son Solomon became the source for most of the proverbs and probably for Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs (Song of Solomon) as well. At some point after the Jews were exiled in Babylon, it seems likely that an inspired scribal editor (perhaps Ezra) pulled the texts together, edited them, and arranged them into a collection that was substantially the same as the Old Testament we possess today.[2]

The authors of certain Old Testament books are unknown to us, but this truth doesn’t diminish the authority of these texts. The authority of the Old Testament doesn’t depend on whether we know details about every human writer. The Old Testament is the divinely inspired history of the people that God chose to prepare the way for Jesus the Messiah. The authority of the Old Testament text is rooted in God’s covenant with Israel and in Jesus’ recognition that these writings were the inspired revelation of his Father.

[1] The glory of God was removed from the temple prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC (Ezekiel 8:6–10:18) suggesting perhaps that articles such as the ark of the covenant could now be touched and taken by other nations. According to Chronicles, every article from the temple was removed and taken to Babylon (2 Chronicles 36:18); however, the ark is not listed when the articles are returned (Ezra 1:7–11). This omission might suggest either that the ark was lost between the removal and the return (for this assumption, see apocryphal text 4 Ezra 10:19–22) or that the ark was hidden prior to the Babylonian invasion (for this possibility, see apocryphal text 2 Maccabees 2:4–10).

[2] See Irenaeus of Lyons, Adversus Haereses, 3:21:2. For defense of the notion that the Psalms in particular were intentionally ordered by a later editor, see Robert Cole, Psalms 1-2: Gateway to the Psalter, Hebrew Bible Monographs 37 (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2012).