In 1415, a church council gathered in the city of Constance. One of the items on their agenda was a heresy trial. In addition to ending a decades-long multiplicity of popes, the Council of Constance concluded that two particular priests had turned into heretics and that both of them must be burned.

There was, however, one slight problem with their desire to torch both priests at the stake.

One of the priests was already dead.

John Wycliffe had passed away peacefully more than thirty years ago.

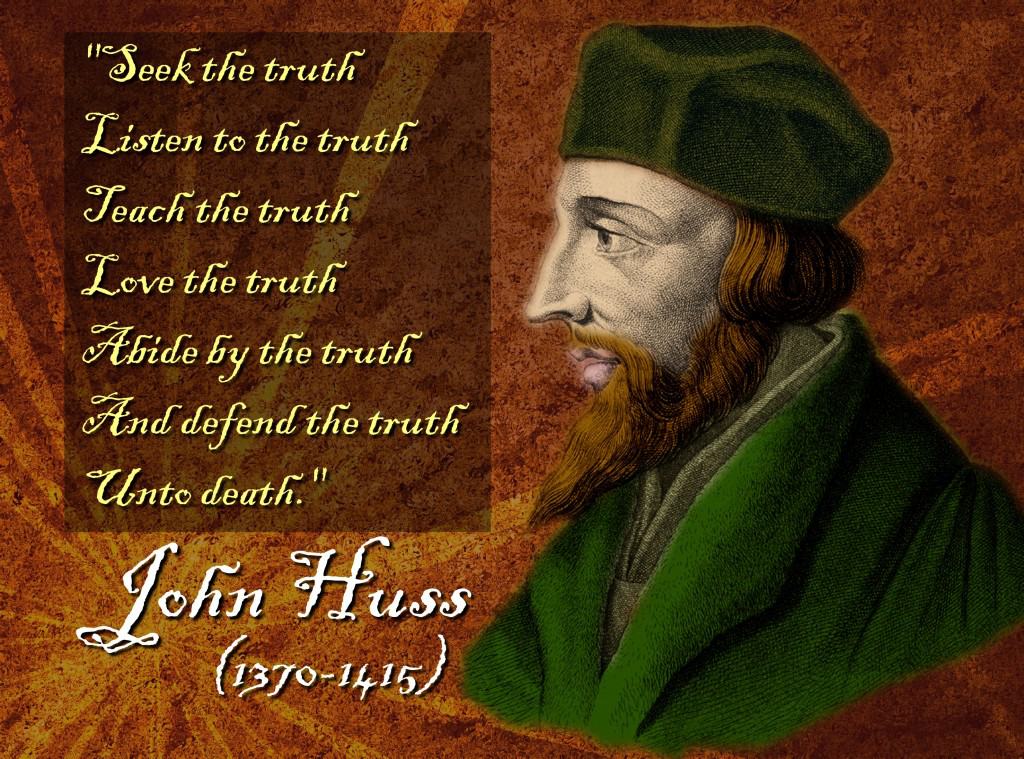

And so, the bishops did what any sensible church council intent on scorching a heretic would do. They decreed that Wycliffe’s corpse would be pulled from the grave, burned at the stake, and then pitched in the River Swift. The other priest, a Bohemian scholar named Jan Hus, was not quite so fortunate. Hus was still breathing when the executioner lit the branches beneath his feet.

(By the way, if you were to write a song rhapsodizing the martyrdom of Hus, you could call it “the Bohemian’s Rhapsody,” and that would be amazing.)

So what did Wycliffe and Hus do to deserve this fate?

Wycliffe was one of the most brilliant scholars of the fourteenth century, and everyone knew it. When he received his doctoral degree from Oxford University in 1372, he was already recognized as a leading theologian—but his views grew increasingly out of step with the established church.

In time, Wycliffe came to a conclusion that may sound like common sense to us today—but it was a radical claim in the fourteenth century: Scripture, not church tradition, is the final authority in every circumstance and every situation. “Neither the testimony of Augustine nor Jerome nor any other saint should be accepted except insofar as it is based on Scripture,” Wycliffe claimed. “Christ’s law is best and Christ’s law is enough.” Since Scripture provides an infallible guide for the Christian life, every Christian—not just the clergy—ought to know the Scriptures. It was this conviction that drove John Wycliffe to have the Scriptures translated into English.

“Wycliffe, By…Translating the Bible, Made It Common to All…Even to Women!”

In 1374, John Wycliffe became a pastor in the English market town of Lutterworth. From here, Wycliffe sent out “poor preachers” to teach the truths of Scripture in the villages of England. Wycliffe provided his preachers with sermon outlines and Scripture paraphrases to teach the people—all in English. “Christ and his apostles taught the people in the language best known to them,” Wycliffe reasoned. “Therefore, the doctrine should be not only in Latin but also in the [common] tongue.”

But John Wycliffe wanted to go beyond merely teaching in the common tongue; he became determined that the ordinary people of England should enjoy direct access to the very words of God. And so, he began the process of turning the Latin Vulgate into ordinary English.

Now, Wycliffe didn’t actually translate the Bible. Instead, he used his position as a scholar and pastor to have the Bible translated in English. The first edition of the Wycliffe Bible began to circulate in 1382. This edition was little more than a rough word-by-word rendering of the Latin Vulgate into English. Still, for the first time since the dawn of the English language, it was possible to read the entire Bible in English. Smoother English readings followed in later editions.

Wycliffe’s work was not well-received by church leaders. “Christ gave his Gospel to the clergy and the learned doctors of the Church so that they might give it to the laypeople,” one of the church’s chroniclers contended. “But this Master John Wycliffe translated the Gospel from Latin into the English. … And Wycliffe, by thus translating the Bible, made it…common to all,…even to women!”

The words of the Archbishop of Canterbury were even harsher: “That pestilent and most wretched John Wycliffe, of damnable memory, a child of the old devil…crowned his wickedness by translating the Scriptures” into English.

“The Ashes of Wycliffe Are the Emblem of His Doctrine”

Three times, John Wycliffe was accused of heresy. Each time, the verdict was derailed before the priest could be condemned and executed. In 1382, an earthquake rocked the city of London during his hearing, convincing many that God himself had taken Wycliffe’s side! The assembly of church leaders convicted Wycliffe anyway, but the favor of the courts and the Parliament kept him from being condemned. In 1384, Wycliffe suffered a stroke while celebrating the Lord’s Supper. The priest of Lutterworth died a few days later, still officially in good standing with his church.

A few years after the Council of Constance condemned Wycliffe in 1415, Wycliffe’s body was exhumed and burned. His ashes were dumped into the River Swift which—in the words of a later chronicler—“conveyed his ashes … into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine which now is dispersed the world over.” A Bohemian priest named Jan Hus was one of those whose thinking was transformed when he read the words of Wycliffe.

What Happens When You Roast a Lean Goose

Influenced by Wycliffe, Jan Hus freely proclaimed the Scriptures to his people and treated biblical preaching as a mark of the true church—and it was this sort of preaching that caused the Council of Constance to silence him by burning him alive. According to a later legend, Hus—whose name meant “goose”—said to his accusers on the day of his death, “Today you will roast a lean goose, but a hundred years from now you will hear a swan sing, whom you will leave unroasted and no trap or net will catch him for you.”

One hundred years later, a German monk rummaging in a library ran across a book of Jan Hus’ sermons and asked himself, “For what cause did they burn so great a man? He explained the Scriptures with so much gravity and skill.” The German monk’s name was Martin Luther. After Luther was declared a heretic and went into hiding in 1521, the first project he undertook was one that would have made Hus and Wycliffe smile: Martin Luther translated the New Testament into German, the language of his people.

Learn more about the history of the English Bible in my book and video series How We Got the Bible.