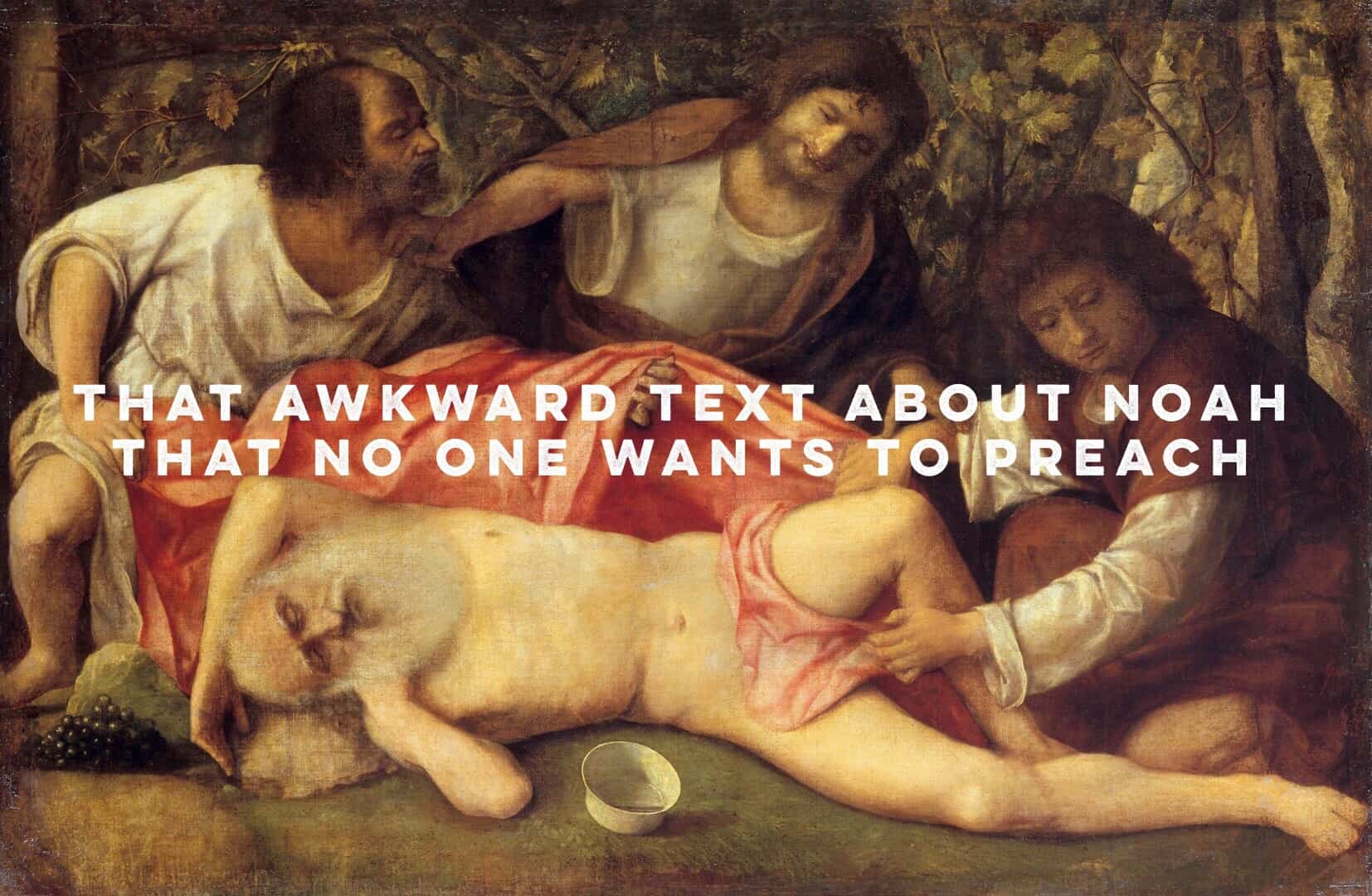

In every Sunday School lesson and Bible storybook about Noah that I recall from my childhood, the ark-builder’s story ended in triumph. In sermons, if they mentioned this text at all, it ended with a “curse of Ham.”

Noah saves the animals and sees the sign of God’s covenant—and, with that, the account of Noah comes to a close with the ark behind him, a sacrifice in front of him, and a rainbow above him. It’s a glorious scene, well-fitted for colorful full-page paintings in Bible story books.

But then, sometime in my late teenage years, I read the rest of Noah’s story.

I quickly learned that the author of Genesis didn’t end Noah’s story the same way as the censors who oversaw the production of Sunday School lessons in the 1970s. The ending of this story is indeed colorful—but not in the same way as those paintings in Bible story books. And then, I realized that this text was also the source of “the curse of Ham” that I had heard pastors cite to smear a veneer of Scripture over their degrading and paternalistic attitudes toward African Americans.

Suddenly, the story of Noah turned out to be far less heroic than I had assumed.

“Noah Wakes Up with a Hangover and Can’t Find His Clothes”: How the Bible Story They Never Told You in Sunday School Was Twisted into the “Curse of Ham”

All of which is why, when Beau Hughes at The Village Church in Denton gave me the opportunity to preach this text, I was simultaneously delighted and a bit concerned. I had taught portions of Genesis before, but I had never preached this particular text. As I prepared this message, I wanted people to feel the awful weight of this text—both because of the events in the text itself and because of the racist appropriations of the text that came later—but I wanted that weight to turn the people’s attention away from Noah and toward our deep need for Jesus.

Here’s the message that I preached at The Village Church in Denton:

Audio Player(If the audio player doesn’t work on your device, click here: “The Curse of Noah and the Blessing of Christ.”)

In his book Peculiar Treasures, Frederick Buechner described the closing scene of Noah’s story with characteristic eloquence:

“Never again,” God had said, and Noah clung on to those words like a raft in a high sea.

With the rainbow tied around his little finger to jog his memory, surely God would never forget what he’d said. No matter what new meanness people might think up, surely the terrible thing would never happen again. As an expert in hoping against hope, the old sailor told himself that the worst was over and that as sure as God made little green apples, a new, green world would blossom up out of the sodden wreckage of the old.

He then planted the first vineyard and invented wine. The way he figured it, wine would help him forget the dark past and, if all went well, would be like the champagne at a wedding that you toast the future with. And if all did not go well, if doubts and fears began to gather like rain clouds in his heart, then wine would help him ride out the storm within as before he’d ridden out the forty days and forty nights.

In the meantime, he would keep his eye on the rainbow and his hand near the corkscrew and try to be fruitful and multiply just the way God had told him and his seven-time great-grandfather Adam before him.

Maybe it happened that way, maybe it didn’t, but Buechner’s re-telling skillfully highlights the faithfulness of God that’s imprinted in every line of this text. In this sermon, I invite you to listen for the echoes of that faithfulness in the midst of humanity’s repeated rebellion and misuse of God’s Word to promote a “curse of Ham.”

Discuss in the Comments:

Listen to this message that I shared at The Village. What did you learn that you never understood before? Had you heard about the supposed “curse of Ham”? How did this message help you to understand how Scripture has been distorted to support systemic racism in the United States?